Quick: Training!

What’s your first reaction?

Love it? Hate it? Somewhere in the middle?

All training is not created equal, and training to handle challenging situations can be deep, time intensive, and provoke a new level of growth for you and your team. When that’s the case, the skeptic becomes a supporter and your team grows.

Keeping the momentum going after a successful training program is usually the hardest part. It requires commitment and dedication, buy-in from your critical players, and constant reminders.

Team problem-solving is one of those complicated topics because it often focuses on moving through difficult moments. It’s complicated because teams are complicated – they’re full of people!

Sometimes, the complexity that is so useful in teaching the skills of problem solving gets in the way of the long-term application.

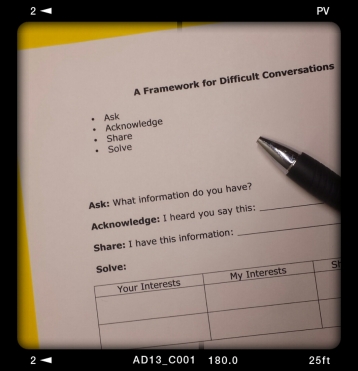

I’ve boiled several aspects of team-focused problem solving methods down to four words:

- Ask

- Acknowledge

- Share

- Solve

Ask: What information do you have?

Acknowledge: I heard you say this: ________________________

Share: I have this information: ______________________

Solve:

| Your Interests | My Interests | Shared Interests |

This approach, which is common to many systems for team communications, helps me

- Focus on interests, not positions.

- Be an active listener. (here’s a fun example: Hostage & Crisis Negotiators)

- Share my unspoken thoughts, and to remember that others have them too. (One example of the left-column method)

I also try to remember one primary point of ! Caution !

Don’t do this: make assumptions about your partner’s inner state.

Example: “You were angry when I told you what I thought about our interview candidate”

Instead, do this:

Ask: “I saw you frown when I said I thought they were well qualified. Were you reacting to my statement or something else?”

Once you start to listen for it, you hear a lot of assumptions about why people are doing things (they don’t like so-and-so, they’re preoccupied with something else, they’re not skilled enough). These assumptions are just that: your assumption, not a fact.

Check yourself but asking how you’d react if someone stated that “fact” about you. You may be surprised to see how often you make these types of assumptions.

Here’s an example of the four questions in action.

The Setup:

Sandy has been given responsibility for managing three divisions that have not been performing well. She’s an up-and-coming worker in her organization but this is new territory for her. She’s had to learn new operations, build relationships, and try to sort through the opinions, facts, and the mountain of data that her division chiefs have brought to her in the past three months. Late on Friday, her boss, Ross, lets her know there’s a gap on the Board meeting agenda and he’d like Sandy to present an update.

Sandy doesn’t feel ready and tells her boss she thinks they’ll have better news next month.

What’s really going on?

Take a look at what Sandy’s NOT saying: I’m concerned that our numbers don’t look good and I won’t have a chance to talk to our managers in all three divisions before the Board meets on Tuesday. One has been out sick, one is on vacation and the other one always bombards me with data and spreadsheets instead of sharing real information. I’m worried that I won’t be prepared to answer questions and the Board will doubt my ability to manage this key transition. I don’t want to let my boss down by doing a bad job.

And what Ross is NOT saying: I’d like to fill the agenda for the meeting next week, and Sandy is always willing to help out. If I can get her to just let them know we’re on it, the Board will probably ask me fewer questions between now and our next full update. I don’t want to have a hole in my agenda next week and I’m upset that Jason’s group bailed on me at the last minute, putting me in this position.

It’s easy to imagine that a short conversation could result in something like this:

- Sandy asks what about an update to the Board is important to Ross.

- Ross says he just needs to give them something.

- Sandy acknowledges that he wants to update them and shares her concerns about communication with her group and how it will look to the Board if she has incomplete information.

- Ross asks what she could do by Tuesday.

- Sandy says she has preliminary information about what’s been done so far and she thinks she’ll have data in a week.

- Ross acknowledges she’s not going to be ready on Tuesday and shares that he primarily needs to fill a hole in the agenda.

- Sandy’s interests are good data and being professional for the Board.

- Ross’s interests are good data and keeping the meeting running smoothly.

- Together they solve the situation by agreeing on a preview-presentation at the meeting with a report to follow.

It’s a better outcome for them both, and avoids a weekend of stewing about uncooperative staff and worrying about an upcoming presentation.

I hope Ask-Acknowledge-Share-Solve works for you.